Over the past several months, I have had a few discussions about the literality of the Bible with a fundamental Christian. Although I am a priest and he is a lay person, we have different ideas of how to interpret the Bible and who actually wrote Scripture. I think he believes God, Himself, took quill to papyrus and wrote the Bible as we know it today. I would like to try to explain the academic study of the Bible, from a historical perspective. I am a Jesuit priest with an extensive background in religious studies. My expertise is in ancient Christianity — 1st Century Christians — and the ancient writings that were eventually, several hundred years later, canonized into what we now call The Holy Bible. I have wondered if my fundamentalist friend is clear on the problems we have with ALL translations. So, here goes . . . .

The Bible Is a Written Document

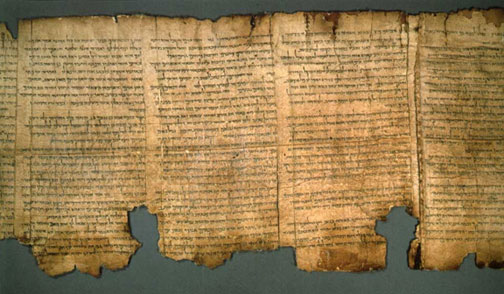

Scripture, although divinely inspired, was not literally written by God. He did not sit down with papyrus and quill in hand to write The Word. Scripture was written in human words by human hands, being passed on and saved for future generations by being hand-copied time and again when older copies became worn out and faded. Even with the invention of the Gutenberg printing press in about 1450, allowing Bibles and other materials to be printed en masse, human mistakes were made. The scribes of old ran even greater risks of error when they hand copied manuscripts. We, in the 21st century, would like to believe the scribes were professional perfectionists. It is possible many were, but it is also possible some of the scribes had only limited knowledge of what they were copying. They were not saved by divine help from making mistakes. The science of detecting what is wrong with the text, and either looking for a better and more accurate manuscript or suggesting a better reading by means of trained guesswork, is called “textual criticism.” All translations attempt to give sensible meaning to every line in the Bible, even if the Hebrew text is a mess. An exact understanding of the Bible requires an ability to do textual criticism, as well as to have a working knowledge of the original language(s) in which the texts were written. Everyone who studies the Bible can draw on the results of good scholarship through a number of ways:

- Modern translations which are generally all quite accurate.

- The text notes that accompany a good study Bible give valuable background information, point out problems with the original text, and explain difficult terms.

- There are many commentaries on individual books of the Bible available for deeper study. A good commentary will not only explain the Biblical author’s thought process, but also will offer theological insights into the meaning of the text for Christians and Jews.

Textual Criticism

The first responsibility of Biblical scholars is to make sure that the text handed down to us from ancient times is the best and most accurate possible. Making this job difficult is that ancient Hebrew was written in consonants only, leaving out the vowels. When translated into English, the meaning can change depending on which vowel is inserted. For example, if we see, “Kng Dvd lvd,” does it mean King David lived (דוד המלך חי) or King David loved (דוד המלך אהב)? Many Hebrew texts include similar difficulties. Because the ancients possessed no printing press, ALL literature was hand copied, and there were no proofreaders to check the spelling before the book was published. A scribe usually copied from an older manuscript, and if he got tired or distracted, he could either omit part of his text or copy it twice. Dittography, or “written twice,” was a common error in copying the Bible. For example, in 2 Kings 18:17, the present Hebrew Bible reads:

מלך אשור שלח את המפקד לחזקיהו, בחיל כבד לירושלים, והם עלו והגיעו לירושלים והם עלו והגיעו למקום ועמדו על הערוץ של הבריכה העליונה.

The king of Assyria sent the commander to Hezekiah with a great army up to Jerusalem, and they went up and arrived at Jerusalem and they went up and arrived and stood at the channel of the upper pool.

Fooled by the two occurrences of Jerusalem, the scribe looked back down and began copying from the first occurrence, thus repeating himself.

Sometimes scribes copied by dictation as someone read to them. Words that sounded alike occasionally got confused — just as in English, where people sometimes write their for there or they’re, so too, we find in the Bible the preposition al (upon) often confused for el (to, for). Another common mistake stems from sloppy handwriting — just like today. Many letters in Hebrew script look alike, and when scribes were tired or in a hurry, letters could easily be confused which may affect the meaning of the word. For example, in English, if we do not close the loop on our “g,” it looks like “y.” Then, “bog” becomes “boy” and “tog” becomes “toy.” The meaning of the sentence then changes. A very common practice in writing ancient Hebrew is that, often, scribes did not space between words. In Jeremiah 46:15, the Hebrew text has the consonants nshp which can mean, “it was swept away (הוא נסחף ).” This makes a certain amount of sense, but since Jeremiah was addressing Egypt, scholars see a much clearer meaning if the word is divided in two: ns hp. “Why has the bull fled (למה את השור ברח)?” Jeremiah issues a strong condemnation of idolatry through worship of the sacred bull, a well-known practice from ancient Egyptian history.

Sometimes scribes copied by dictation as someone read to them. Words that sounded alike occasionally got confused — just as in English, where people sometimes write their for there or they’re, so too, we find in the Bible the preposition al (upon) often confused for el (to, for). Another common mistake stems from sloppy handwriting — just like today. Many letters in Hebrew script look alike, and when scribes were tired or in a hurry, letters could easily be confused which may affect the meaning of the word. For example, in English, if we do not close the loop on our “g,” it looks like “y.” Then, “bog” becomes “boy” and “tog” becomes “toy.” The meaning of the sentence then changes. A very common practice in writing ancient Hebrew is that, often, scribes did not space between words. In Jeremiah 46:15, the Hebrew text has the consonants nshp which can mean, “it was swept away (הוא נסחף ).” This makes a certain amount of sense, but since Jeremiah was addressing Egypt, scholars see a much clearer meaning if the word is divided in two: ns hp. “Why has the bull fled (למה את השור ברח)?” Jeremiah issues a strong condemnation of idolatry through worship of the sacred bull, a well-known practice from ancient Egyptian history.

A final difficulty in translations is caused not by mistakes as much as by intentional additions. Books were expensive when hand copied, and readers often put important comments and critiques directly in the margins of a manuscript. If they, themselves, found a copy error from the past, they would write the correct words above the line. Since in  ancient times, books did not have pages with wide margins, but were written in columns on a long scroll, the space was very cramped and added words often touched against the original text. Later copyists sometimes added the marginal comments right into their new text, either by mistake or because they honestly believed an earlier scribe had accidentally left them out of their document while copying and had put them in the margin at a later time.

ancient times, books did not have pages with wide margins, but were written in columns on a long scroll, the space was very cramped and added words often touched against the original text. Later copyists sometimes added the marginal comments right into their new text, either by mistake or because they honestly believed an earlier scribe had accidentally left them out of their document while copying and had put them in the margin at a later time.

Text scholars must compare many ancient manuscripts of a given book in order to establish the best reading from the oldest sources possible. If this proves impossible because the text seems corrupted as far back as copies exist, they must suggest possible changes which they think reflect the more original text. Text critics do not just guess, but use their best professional judgement. They compare ancient translations, such as Greek or Syriac, to see if the ancient translators used a better manuscript than we now possess. Because ancient peoples were highly traditional in their use of language, attention to the neighboring tongues can prevent the textual scholar from changing or removing a word unnecessarily.

Caution should guide changing any ancient literary work, for we are not Hebrews of old, and what we think religious ideas should be for our day may not be how the ancients thought. In the 20th Century, too many scholars were led by their own philosophy or particular dogmatic creed to decide that difficult Biblical texts had to say one thing or another. Eisegesis is when interpreters read their own ideas into a text, or use the text all twisted around to defend some modern meaning. Eisegesis differs widely from proper interpretation of the text, which we call exegesis, or reading from the text itself.

Text Traditions

There were quite a variety of copies of the Hebrew Bible available by the time of Jesus. Scribes had been copying for hundreds of years, thus there were many different editions being circulated, some longer with sections added and some shorter with sections omitted. ALL had some change or error in them. Since a scribe in one area often copied from a local text, the same error or change often appeared regularly in one place, e.g., Babylon, but not in texts copied in Egypt. Thus, at the time of Christ, three major “families,” or groupings, of text types could be found: Babylonian, Palestinian, and Egyptian. The Babylonian Jews, for example, treasured their texts which had a very short, tightly-knit edition of the Pentateuch, while Egyptian Jews used a richer and more expanded text. Only at the end of the first century CE did the rabbis decide to end the confusion and select one text. In the Pentateuch, they chose the Babylonian tradition, but in other books, such as the prophets Jeremiah and Isaiah, they followed the Palestinian text.

same error or change often appeared regularly in one place, e.g., Babylon, but not in texts copied in Egypt. Thus, at the time of Christ, three major “families,” or groupings, of text types could be found: Babylonian, Palestinian, and Egyptian. The Babylonian Jews, for example, treasured their texts which had a very short, tightly-knit edition of the Pentateuch, while Egyptian Jews used a richer and more expanded text. Only at the end of the first century CE did the rabbis decide to end the confusion and select one text. In the Pentateuch, they chose the Babylonian tradition, but in other books, such as the prophets Jeremiah and Isaiah, they followed the Palestinian text.

These first century rabbis also inaugurated a method of guarding the text from future glosses and additions, though not completely from copying errors. They counted word, syllables, and sections, and wrote the totals at the end of each book of the Hebrew Bible. These could be checked in later copies to see if the numbers corresponded exactly. The system worked, helping to preserve a good text and paving the way for the addition of vowels to the text — a need that was becoming very acute as fewer and fewer readers were familiar with the Hebrew language.

Versions

The standard Hebrew text that resulted from the decision of these early rabbis has become known as the Masoretic Text (MT), named after a later group of Jewish scholars of the eighth to eleventh centuries CE — Masoretic, or interpreters, who put vowels into the text and, thus, “fixed” the words in a definitive form. No longer could a reader be confused by whether the word qtl in the text meant qotel, “the killer”, or qatal, “he killed.” The Masoretes worked carefully from the best available tradition of textual interpretation and made the task of later readers much easier. Any Biblical scholar will admit the great debt he/she owes these Jewish experts. However, at times, having such a fixed text raises more problems than it solves. After all, the Masoretes lived 1,000 years after the major writing of the Hebrew Scripture, and many words had changed their meaning and grammatical shape over the centuries — much like our own English language continually evolves from one generation to the next. Later generations simply did not understand the proper meaning of a passage. That is why the task of the textual critic continues today.

Besides the use of the previously mentioned scientific tools, text critics can gain much help from other ancient translations of the Hebrew into Greek, Syriac, Latin, and Aramaic. The most important of these are:

- Septuagint (LXX) — The Greek translation of the entire Hebrew scripture and all of the deuterocanonical books. It was widely used by the Jews outside of Palestine (the diaspora), and especially the New Testament writers and early Christians. Because of its age, it offers valuable help in resolving discrepancies in ancient Hebrew texts.

- Peshitta — The ancient Syriac version of the Bible, used in Syriac-speaking Christian countries from the early 5th century and still the official Bible of the Syrian Christian Churches.

- Vulgate — St. Jerome’s careful Latin translation made in the 5th Century CE, following the Hebrew text as closely as possible. Jerome had help from Palestinian Jews in his translation. The Vulgate gained a position of honor because it became the common (vulgate) Bible of the Western Church during the Middle Ages.

- Targum — An ancient Aramaic paraphrase or interpretation of the Hebrew Bible, of a type made from about the 1st Century CE when Hebrew was declining as a spoken language.

The Bible as Literature and Story

The Bible is much more than a “text” to be restored to its original beauty; it is the literature of a living people. Because authors in every age and every culture express themselves differently, modern literary theory must offer ways of understanding ancient writers. There is, for example, the basic distinction between poetry and prose. Some thoughts are best expressed in poetry: love songs, hymns, intense pain of sorrow and loss. Others are better expressed in prose: biographies, historical records, and lists. What type an author selects is determined by how he feels that he can best communicate what he wants to say.

Even these categories may be easily broken down into more limited ones. For example, a list may be a “king list,” giving the names and dates of the rulers of a nation, or a genealogy list showing someone’s ancestors, and so forth. Hymns may be hymns of joy or lament, or songs of thanksgiving, or of praise of God’s creation such as Psalm 148, which is almost a list. A sermon may be an impassioned plea, a persuasive appeal, or a thoughtful explanation. In every case, the identification of what type of literature we are dealing with will help us to know much more about the author’s purpose in writing it, for whom it was intended, and from what situation it developed.

Oral Tradition

Communication in the ancient world was mostly oral, and societies that rely on oral tradition look at knowledge and history far differently than do people accustomed to reading. First of all, cultures who  utilized oral tradition generally had memories that are better than the memories of modern day peoples who rely on books and the internet for gathering information. The ancient people often heard stories and events told in a communal setting, either on special feast days when religious leaders would recite the ancient traditions, or in schools where masters gave, and interpreted, the laws with vivid examples, or in gatherings for entertainment. Very rarely were any of these stories simply recited by rote memory. Traditions were constantly updated a

utilized oral tradition generally had memories that are better than the memories of modern day peoples who rely on books and the internet for gathering information. The ancient people often heard stories and events told in a communal setting, either on special feast days when religious leaders would recite the ancient traditions, or in schools where masters gave, and interpreted, the laws with vivid examples, or in gatherings for entertainment. Very rarely were any of these stories simply recited by rote memory. Traditions were constantly updated a

nd enlivened by new examples. Oral style demanded that the storyteller preserve the well-known plot or the basic outline of the facts, but he often varied the details and the order of minor incidents, or even added extra details.

Another factor about oral cultures in the ancient Near East, was their dislike for exact facts and specific dates. The common religious belief was that salvation and wholeness were found in a return to that first moment of creation when all things had been originally perfect. Religion was centred on sacred times of the year. In this world view, remembering the deeds and events of the past year could be a block to achieving union with the moment of divine creation. It does not mean that Babylonians or Assyrians had no sense of their own history; they did, but they expressed it and gave it meaning for themselves by using themes from the great myths about creation, or through reference to the heroic deeds and lives of the great primeval gods, heroes, and kings. The actual details of historical events were far less important to an ordinary person of ancient times than was the pattern by which it was explained and the essential primeval event to which it was compared.

Higher Criticism

Once we recognize the great variety that old traditions take when passed down in an ancient culture, we will understand better the need to develop tools that can identify the types of literature found in different books of the Bible. More importantly, there must be tools to trace how the types changed as they were passed down, what happened when they were put into writing, how many versions of the same story existed, and a host of other questions. Literary analysis is needed to sort out the many layers of religious thought over hundreds of years that are found in the Bible. Not all Biblical books were written at the same time, and there are many older as well as newer levels in them. This supports the declaration of the author of the New Testament letter to the Hebrews that, “In many and various ways God spoke of old to our fathers by the prophets; but in these last days he has spoken to us by a Son. . .” (Heb. 1:1-2).

Even though the books of the Bible are now joined together as one canon that traces the shape our faith has taken from the beginning of the world until the time of the apostles, a serious student of the Bible must understand how Israel grew and changed and deepened its faith. The process of understanding the older layers of thought is done by the use of three literary tools: source criticism, form criticism, and tradition history criticism.

Source Criticism

Source criticism studies the specific problem of whether there are written documents behind the present text. This method has developed over the past several centuries to answer the problems of repetitions and inconsistencies in the Pentateuch. The use of two distinct names for God in Genesis led researchers to conclude that Moses must have used two or more different written sources when he composed the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, and Numbers. Source critics showed the contradictory styles of writing that appeared side-by-side in a single book, e.g., calling the Covenant mountain Sinai in one line and Horeb in the next. Source critics pointed to the repetition of whole incidents a few chapters apart, most famously the two creation stories in Genesis 1 & 2, and the strange tale of how a patriarch lies when telling a foreign king that his wife is really his sister. This story occurs three times: Genesis 12:13, 20:2, and 26:7, twice involving Abraham and once involving Isaac. Even the beginning student might question how such a unique event could happen to Abraham without his learning a lesson, yet he seems to have forgotten everything when the se

cond time arises.

Scholars of the 18th and 19th centuries identified four clear written sources in the first five books of the Bible; the identification of early sources always meant written sources which were gathered together and edited in several stages until the final Pentateuch, as we have it today, emerged. Other examples of sorting through the layers of written sources can be found in Psalms — Psalms 42-83 are referred to as the “Elhoist Psalter” because God is called Elohim (Hebrew for “God”), where most all other Psalms refer to God by his proper name, YHWH. Book of Job is another example of having more than one source — Job 1 & 2, and 42:7-17 are written in a prose folk tale, while the rest of the book is written in poetry. Another inconsistency is where Job and three friends have completed their dialogue with each other and Job has called for God to come, but suddenly a fourth person, Elihu, appears. Elihu speaks in a monologue for four chapters, 33-37; when he finishes, God appears and speaks to Job and the three friends but seems not to know Elihu ever existed. Scholars, thus, believe the Elihu section was an afterthought that was added at a later time.

Form Criticism

Form criticism was devised because of dismay over the excesses of some source critics. Unlike source critics, form critics, such as Herman Gunkel, understood the diversity and inconsistencies in the Pentateuchal narratives as signs of typical oral style. Fundamental to his understanding was the conviction that oral tradition was not carried on by individual authors, but by the community, which had to listen, remember, and carry on the tradition. The literary “forms” that were previously mentioned were the building blocks of an oral society.

Each type of story, tradition, or communication belongs to a very concrete setting in life. Thus, if we can identify a funeral lament, we know it was spoken at the time of a death; joyful marriage songs were sung at weddings, etc. If the scholar can only identify the earliest form that each type took in the ancient Israelite culture, he gains a very good clue to the kind of situation and the period of history in which this unit of traditional material originated. From this point, he can detect a history of additions and growths to the time it was finally written and kept as a document.

The form critic always asks: Who is speaking? Who is the audience? What is being said? Where is it said? What is the purpose? The form critic must ask not only who spoke originally, but who added the additions, and who was the editor who wrote it down, and who revised that edition.

One fundamental aspect of the form critical method is a belief that oral tradition does not change its form rapidly. These are truly “traditional” and tend to keep the same wording and favorite formulas frozen over long periods of time. Community memory for details is not nearly so accurate as is its preservation of the different “forms” themselves. Historical events rapidly find themselves clothed in one special form or another.

A simple way of describing the work of form criticism is to list the following steps:

- Defining the Unit — In order to identify the form of a piece of literature, the form critic must have the whole piece. Our modern bibles often mark off different units by paragraphs or bold-type headings.

- Naming the Form Used — Is the unit a lament? A letter? A saga? This is referred to as naming the literary genre of the unit. If we miss the proper genre or form, we may never find out how it came to be used.

- Describing its Setting in Life — After knowing what form the piece has, we try to identify its original social context and, further, what kind of thinking gave rise to such expression. Can we know something about the people from the way they spoke?

- Identifying the Purpose — The final step seeks what function or purpose this piece served in the original oral stage, and what purpose does it now serve in the larger written work of which it is a part. Can we trace what changes took place in the people of Israel by knowing how these two uses differ?

To simply read the Bible all on one level as though no changes had taken place in Biblical thought over the centuries is to miss the living spirit of Israel’s growing faith. Form criticism seeks to capture that actual growth.

Tradition History

Form criticism, by its nature, includes tracing a text through all levels from the most primitive oral story to the finished product. But, many Biblical scholars became so enthused over the search for the original, simplest oral forms behind the Biblical text that they almost forgot the written and edited stages that we know much more about. In recent years, experts have become more concerned with the total process of growth. They are looking at the various times when the Biblical texts were edited, and the different societies from which the editors came. The positive role of editing, or redaction, of ancient texts is now more appreciated than in the past. No longer do scholars see the redactors as unimaginative bureaucrats pasting together older texts, but as persons passionately involved in the problems and needs of their time, who updated and expressed the traditions to speak to a new generation.

In tradition history, the scholar studies the societies of scribes, wise men, priests, or prophets and how they responded to new situations. There is an effort to pinpoint the diverse interests of each region of Palestine in order to better understand the moments of decisive importance and change, when tradition had to be reworked to meet new needs.

The specific task of tradition history is to trace the use and reuse of Biblical material from their earliest form and settings in the life of Israel down through all the stages of being written and rewritten until it reached the final form as it is now found in our Bibles. Where form criticism alone stresses discovery of the earliest oral units, and source criticism alone stresses the earliest written sources, tradition history particularly concerns itself with the later adaptations and reworking of the text.

The use of such modern historical-critical tools for interpreting and understanding the Bible was at first limited to Protestant Biblical scholars in Germany and England. Catholic scholars, along with Jewish scholars, were reluctant to abandon the ancient traditions of the Church and Synagogue that Moses was the author of the Pentateuch. Source criticism was widely popular among the rationalists and anti-Church thinkers of the 18th and 19th Centuries because it directly challenged the naive beliefs of the faithful. Religious leaders saw these methods as dangers to the faith of the churches. Another area of concern was the 19th Century tendency to see the Scripture as a record of Israel’s growth from superstition under Moses and the judges to the enlightened insights of the prophets to repressive reaction of priestly doctrines.

Many Catholic scholars were attracted to the possibilities of critical methods, but they did little with them until the 1940s. In 1943, Pope Pius XII issued an encyclical letter, Divino Afflante Spiritu, that gave Catholic Biblical scholars encouragement to examine the ancient sources and literary forms in order to deepen the understanding of the sacred texts. From that time on, Catholic scholars have pursued a sober use of source and form criticism as seriously as do most Protestant scholars and many Jewish ones.

Rhetorical Criticism

While form criticism often leads to tearing the Biblical passage down to its smallest unit, the rhetorical critic accents the wholeness and unity of many chapters and books. The rhetorical critic shows that many repetitions or seemingly unusual features can, in fact, add to the dramatic force of stylistic beauty of the work. At the same time, rhetorical criticism brings us closer to the goals of the literary critics who value reading the Bible as a masterpiece of World literature. It reminds us that, despite all the scientific tools we use to understand the Bible, imagination is still the heart of real literary art. The inspired writers of the Bible created with imaginative and carefully chosen phrases to stimulate a response of faith to God’s merciful actions for his people.

As lengthy as this commentary seems it barely covers the surface of the material I have my students read. There are many ways to study the Bible, but to truly understand all that there is to know about the Bible, it is imperative to have a knowledge of the history of Israel and to have a working knowledge of the ancient languages that were used to write the stories we find in the Bible.

God bless all those who study the Bible, to share in God’s holy Word.